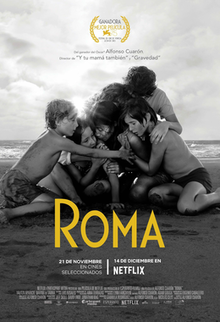

Reliving reality through Roma

Oscar nominated movie based on director’s childhood

The renowned hall of foreign language and indie films in Omaha has always been Film Streams. Walking through those glass doors, I honestly didn’t know what to expect of foreign language film Roma. As the opening credits rolled, I plucked a kernel of popcorn from the precariously placed bag on the blue velvet armrest.

This black and white masterpiece had received as many accolades, including 10 Oscar nominations, as there were half empty Coca-cola bottles on the streets of Mexico City during the shoot. And yet I couldn’t help wondering, how could a story about a servant interacting with her middle-class employers be considered special?

But this speculation was all for nothing. This movie really touched me emotionally, and I genuinely can’t find only one reason why it was truly amazing.

Perhaps the answer lies not in the precise sound editing or the integration of cultural and social issues, but the fact that this beautiful, heartbreaking story is true. Director Alfonso Cuarón grew up in a house in a small neighborhood in Mexico City, 21 Tepeji Street, right across from the actual filming location at 22.

As a boy, Cuarón grew up under the care of a household servant, learning from her struggles as he navigated his own maturity. Roma is a semi-autobiographical portrayal of the struggle-ridden life his family and their servant faced together.

Mrs. Sofia, played by Marina de Tavira, struggles to raise her four children while maintaining her relationship with her husband in the 1970s. At the same time, her servant Cleo, played by Yalitza Aparicio, becomes pregnant without any support as the father has abandoned her.

Their intertwining experiences are represented by Sofia’s quote, “We’re finally alone. No matter what they tell you. Women, we’re always alone.” Along with these internal struggles, the protagonists also face external conflicts as many places in Mexico during this time period were under political duress.

Through these adversarial circumstances and more, Cleo realizes that though she and the family may be broken, they could make each other whole again. And although the pieces don’t completely fit together, they make an imperfect mosaic of experiences, cultures, and life.

Although completely black and white, Roma’s deliberate cinematography needs no color spectrum to capture a scene’s beauty. Each shot is much like a painting, with no pillow unfluffed or book page unturned. Lengthy takes and background sounds allow the viewer to fully imagine and grasp the traumatic events that occur in the movie.

Originally I was skeptical of the subtitles, worrying they would take away from certain movie scenes. But towards the end, I barely noticed them.

Aparicio and de Tavira are nominated rightly so for Best Actress and Best Supporting Actress respectively at the Academy Awards. Delivering witty lines and conducting casual dialogue in Spanish, the actresses bring a sense of companionship and love to the screen.

Groundbreaking films like Roma have become much needed. Because sometimes we desperately need to learn from other people’s stories. Whether at 21 or 22 Tepeji Street, a breathtaking story was born.